Content warning: This article discusses tattooing and tattoo removal techniques, including needles, as well as skin composition.

Have you ever wondered why tattoos are permanent even though skin regenerates constantly? Let’s dig deeper into the skin layers to explore how the immune system and skin cells work together to make tattoos last!

On average, we lose (and gain) 40,000 skin cells a day, which is a lot! You might think tattoos would disappear along with the dead skin cells, but they don’t. After cicatrization, tattoos become slightly less defined and blurrier, but they stay put (unless you go through the painful and lengthy process of tattoo removal).

What are tattoos?

Generally, tattoos are defined as the injection of ink into a person’s skin. This can be done with a handheld needle or a mechanical tattoo gun, although other techniques exist. The precursor of the current mechanical tattoo gun was invented in the 1800s by Samuel O’Reilly, but tattooing is a practice that spans millennia and is practiced worldwide. In some cultures, getting a tattoo was and still is a deeply sacred and spiritual experience.

Did you know? The word “tattoo” comes from the Samoan word “tatau”, to strike.

Since each needle insertion into the skin is a tiny puncture wound, it is very important to consider safety when getting a tattoo. Each puncture wound could lead to infection, an allergic reaction, and there are also risks associated with blood and needles, like transmission of pathogens causing hepatitis, AIDS, tuberculosis, syphilis, etc.

In the US, every tattoo artist is bound by the Bloodborne Pathogens Rule issued by the Environmental Protection Agency, the same as hospitals and doctors’ offices are.

This is why a respectable tattoo artist will always use single-use needles, ink cups, gloves, and ink. They will also take care to practice in sterile conditions by disinfecting. Aftercare is also a very important part of taking care of your tattoo’s cicatrization.

If you want to get a tattoo, please verify that your tattoo artist follows proper procedures and make sure to take care of your skin afterwards.

The skin and its layers

The skin is the body’s largest organ; it protects us from pathogens, rain, dust, the sun, etc, by being a physical barrier between the outside and the inside of our body. It also plays a role in regulating the body’s temperature by sweating and is essential for the sense of touch.

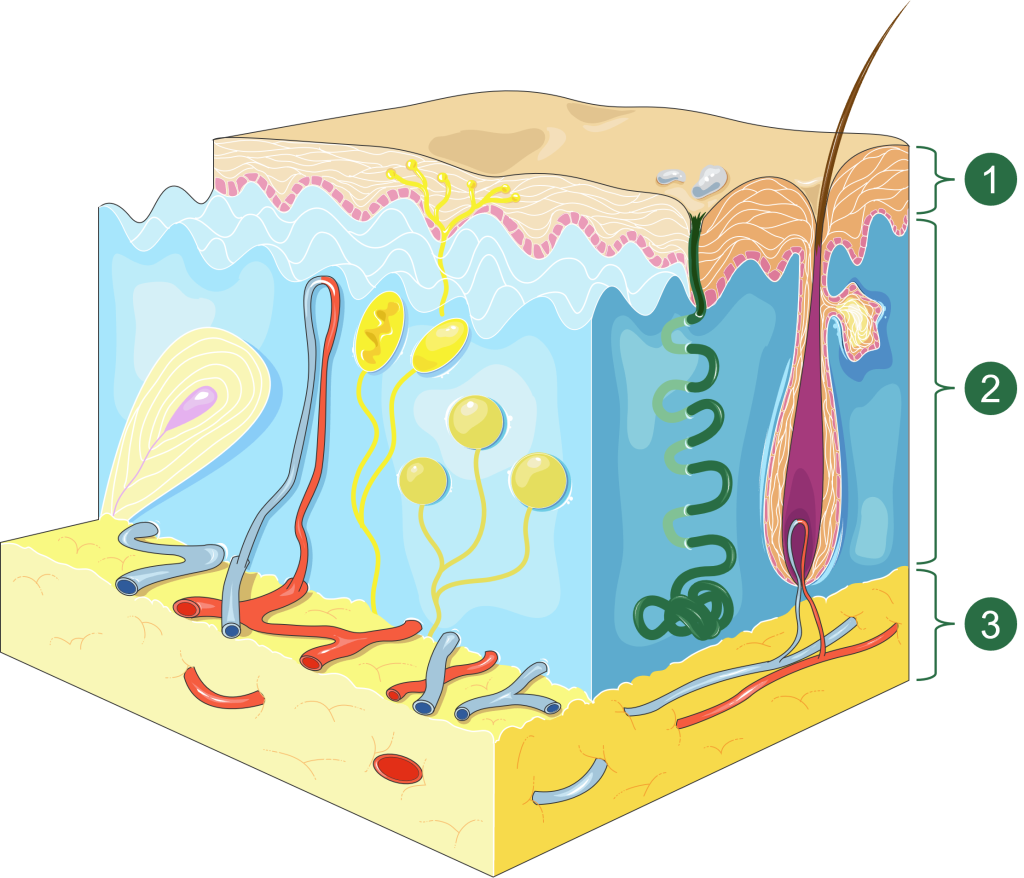

The skin is divided into three main layers:

The top layer is the epidermis, which is the one in contact with the exterior. Therefore, it is quite thin but very sturdy. The cells in this layer are continuously dividing and dying to renew and replace the old skin cells.

The melanin found in this layer helps protect us against the UV rays coming from the sun.

Contrary to the epidermis, which is almost exclusively composed of cells, the next layer, the dermis, is also full of proteins like collagen and elastin. These give the skin resilience and elasticity. The dermis makes up 90% of the skin’s thickness and contains the roots of hair follicles, oil and sweat glands, and nerve endings. The blood vessels in this layer provide the necessary nutrients to the cells in the dermis and epidermis.

The last layer is the hypodermis, a thin fatty layer. It serves primarily as a cushion for the bones and muscles, but also as an anchor between these and the skin. The insulating fat in this layer also helps with temperature regulation.

Mini-game! “Name the skin layer!” Can you remember them? (Answer at the bottom of the article)

License: Servier Medical Art, CC BY 3.0, modified to remove legend.

The cells in the skin are primarily fibroblasts, which are activated connective tissue cells, characterized by their production of proteins such as collagen. Fibroblasts are derived from fibrocytes, which are inactive mesenchymal stem cells that circulate in the peripheral blood. The primary function of stem cells, such as fibrocytes, is to divide themselves in order to renew the cell population and replace the dying cells. Fibrocytes originate from the bone marrow and have the ability to differentiate, or specialize, into multiple lineages. These include adipocytes (fat-storing cells), chondrocytes (cartilage cells), fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts (smooth muscle cells).

Since the skin acts as a physical barrier against the outside world, it is normal for cells of the immune system to be present as sentinels and patrols. Those cells will primarily be macrophages, a type of white blood cell. Their main responsibilities include patrolling tissues against pathogens, phagocytosis (see below), and alerting other cells of the immune system by releasing specific proteins called cytokines, and by presenting antigens, aka bits of potential pathogens.

Professional vs non-professional phagocytosis

One way our body gets rid of unwanted substances or responds to an infection is through a process called phagocytosis. A cell engulfs the target and traps it inside a membrane, then tries to digest the trapped material to recycle it.

Some cells of the immune system are considered professional phagocytic cells (macrophages, neutrophils, immature dendritic cells). This means this is one of their primary functions in the body. Many other cells, such as fibroblasts, are also able to phagocytize, but less well or often, since it is not one of their primary responsibilities. They are considered non-professional phagocytic cells.

What makes tattoos permanent?

The first reason tattoos are permanent is that the ink is mostly delivered to the second skin layer, the dermis, rather than the epidermis, the layer that constantly renews itself. The epidermis gets some of the ink, but the constant cell renewal keeps the ink from settling there permanently. Ink deposited into the hypodermis is affected by the fat, which blurs the tattoo’s lines.

The second factor to consider is the ink’s composition: the pigments, suspended in a carrier solution, are often made from heavy metals, which cannot be digested by the macrophages called to the area by the puncture wounds of the needle.

According to the latest scientific research, macrophages gobble up the pigments (phagocytosis) and store them in specialized sacs, but cannot digest them. When these macrophages eventually die, the pigments are released, only to be engulfed by other macrophages or fibroblasts. Studies show that fibroblasts only take up very small portions of pigments, but they far outnumber macrophages, and their combined uptake eventually surpasses the combined uptake of macrophages. This cycle of uptake and release helps explain why the tattoos’ outline becomes blurrier and paler with time.

Another possibly complementary theory states that in cases where there is too much pigment to eliminate in an area, macrophages might form a retaining wall to sequester the pigment outside of themselves instead of trying to eliminate it by phagocytosis.

Tattoos removal

The most common method for tattoo removal is by far the LASER (Light Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation), which has the lowest risk of scarring. To remove a tattoo, short pulse lasers will blast large chunks of ink into smaller bits, ready to be gobbled up by new macrophages then eliminated into the lymphatic system over the next few weeks. These intense short pulses pass through the top layer of the skin and selectively absorb into the pigments.

The wavelengths used are specifically chosen to avoid damaging the skin and the normal skin pigments (the melanin). It is easier to remove black pigments compared to yellow and green for example, because black absorbs all wavelengths.

The laser removal technology is less invasive than the tattoo process since it does not pierce the skin, but it is still recommended to have it done only in approved and regulated clinics, by medically trained professionals. It can be expensive and painful, and complete removal of the tattoo is not really possible, however it is possible to make it fade enough to not really see it anymore.

Tattoos may fade, blur, or even be lightened, but they never truly disappear. The ink embedded in the dermis stays there, carried by your macrophages and fibroblasts for years to come.

Now you know: your skin’s got a secret team of cells working to keep your art alive.

Mini-game answer (click me!)

- Epidermis

- Dermis

- Hypodermis

Sources

- Synapse – Why Tattoos Stay Put

- HowStuffWorks – How Tattoos Work

- HowStuffWorks – How Tattoo Removal Works

- The Fall – How Tattoos Work: Everything You Need To Know

- News Medical Life Science – What are Fibroblasts?

- Premium Tattoo Removal – How does Tattooing work?

- Cleveland Clinic – Skin

- Hank Green explains the very top of the skin

Rabbithole starter

- Nature – Non-professional phagocytosis: a general feature of normal tissue cells & Immunology & Cell Biology – Not an immune cell, but they may act like one—cells with immune properties outside the immune system Two research articles about non-professional phagocytosis (non-centered on fibroblasts), second one is denser

- Journal of Experimental Medicine – Unveiling skin macrophage dynamics explains both tattoo persistence and strenuous removal A research article about the role of macrophages ; Link to PDF (4.4 MB)

- Dermatology – Macrophages and Fibroblasts Differentially Contribute to Tattoo Stability: A research article sadly not in open access ; Shows the difference in quantity of pigment in macrophages and fibroblasts

- Milo from Miniminuteman on Mummy Tattoos – TW: Image and video clips of mummified remains and needles

- Kurzgesagt on Tattoo Removal – TW: animated clips of tattooing, lasers, and cell death

- Institute of Human Anatomy on Tattoos – TW: Image and video clips of human skin, needles, and tattoing